By Cadence Quaranta and Emmanuel Kizito

The phone calls started pouring into a hotline operated by the nonprofit Florida Immigrant Coalition in 2019.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) had just signed a new law, similar to those passed in Texas, Arizona and other states, that required local law enforcement agencies to cooperate with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, despite so-called sanctuary policies that limit interaction with federal agents.

The number of calls to the coalition’s hotline soared from about 100 a month in 2018 to 1,000 a month after the law passed, said Laura Muñoz, the group’s director of services. Many callers were victims of crime or domestic violence who were afraid to seek help from police, Muñoz said. Others needed guidance after encounters with law enforcement.

Their stories did not surprise the coalition and other immigration watchdog groups, which sued the state alleging that the law discriminates against undocumented immigrants.

In September, a federal judge struck down significant portions of the law, saying in a ruling that the statute was “racially motivated.” Judge Beth Bloom said the state’s claim that the law was designed primarily as a public safety measure was unsupported by crime statistics. She also noted the involvement of what she described as anti-immigrant hate groups in drafting the contentious statute.

State Sen. Joe Gruters, chairman of the Florida Republican Party, told Reuters after the decision, “I look forward to this ruling being overturned.”

The state has appealed to the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

The ruling did not appear to deter DeSantis, who has said he plans to expand the anti-sanctuary policies established in the 2019 law. DeSantis has defended the law as being about “public safety, not about politics.”

Local watchdog groups say the law had sweeping implications.

At the Hope CommUnity Center, a group serving immigrants and the working poor in Apopka, Fla., about 20 miles northwest of Orlando, immigrants told staff members that relatives had been detained and moved into federal custody. They needed help finding lawyers, finding family members, finding answers.

Laura Pichardo-Cruz, the center’s executive director, said with former President Trump in the White House and DeSantis as governor, it was “a really terrible time to be an immigrant in America.

“In Florida, it is doubled because we had a really unfriendly federal government and then a very unfriendly state administration,” she said.

Some Florida law enforcement agents moved quickly after the law was passed.

Eight counties detained a total of more than 200 people in fewer than two years — nearly a quarter for traffic violations and most for nonviolent crimes, according to Allan Lichtman, an American University history professor who served as an expert witness on behalf of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit.

“For a lot of people, it felt like law enforcement was being given permission to target them,” said Nezahualcoyotl “Neza” Xiuhtecutli, general coordinator of the Farmworkers Association of Florida, a statewide nonprofit representing workers of color. “The end effect was that it made immigrant communities live in fear.”

In Apopka, Pichardo-Cruz said immigrants have reported an increased police presence in some neighborhoods with high immigrant populations.

“We know that local law enforcement is aware of where immigrants shop, where they live, where they work, the roads they take to work,” Pichardo-Cruz said.

In recent years, ICE has increased its presence in Florida in other ways.

In 2019, Pinellas County Sheriff Bob Gualtieri helped promote the Warrant Service Officer (WSO) program, which allows local law enforcement officers to serve ICE warrants to people in jails. The first WSO agreement was launched in Pinellas County about a month before DeSantis signed the anti-sanctuary bill.

Gualtieri has argued that the WSO program will help deputies fulfill the requirements laid out in the new law.

More than 40 Florida counties currently participate in the WSO program, which has spread to Wisconsin, North Carolina and other states.

The WSO program is voluntary. The law signed by DeSantis, however, mandates all local law enforcement to cooperate with ICE even if local officials oppose the idea.

Madison Muller contributed to this report.

By Jacquelyne Germain

During the Trump administration, opposition to U.S. immigration policy conjured up images of illegal migrants with criminal backgrounds wreaking havoc on America’s legal system.

“They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists,” the former president said in his 2015 announcement to seek office.

Six years later, two Republican lawmakers have created images of immigrants preying on a different target: the environment.

In mid-March, U.S. Reps. Paul Gosar (R-Ariz.) and Bruce Westerman (R-Ark.) penned a letter to Department of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, demanding to know whether the surge of thousands of migrants at the southern border was posing risks to wildlife and turning federal lands into dumping sites.

The representatives cited fears about trash left behind by migrants and the vandalism of American homes and businesses.

“We cannot ignore the environmental impact of illegal migrants when devising immigration enforcement policy,” wrote the representatives, who, at the time both sat on the House Committee on Natural Resources. In November, the House voted to remove Gosar from committee assignments after he tweeted an altered anime video that depicted him killing Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) and swinging swords at President Joe Biden.

For decades, groups pressing to limit immigration have advanced a link between immigration, overpopulation and damage to the environment, building on a legacy of past environmental eugenicists and eco-nativists. Websites have long included images of pristine national parks, mountains and waterfalls.

Now, with Biden promising sweeping changes to the U.S. immigration system, some groups and politicians are once again warning that America’s parks, roads and neighborhoods will suffer.

“I see it as the same old story,” said Lisa Sun-Hee Park, an Asian American studies professor at the University of California Santa Barbara who wrote a book about the environment, immigration and social inequality. “It’s not that hard for us to figure out what is actually going on underneath.”

Early conservationists who worried about the pollution of natural lands frequently talked about the threat immigrants posed to a predominantly white America, said John Hultgren, an author and environmental politics professor at Bennington College in Vermont.

“There was a really close connection between nature and the nation,” Hultgren said. “Something that was perceived to be a threat to one was automatically filtered through that prism and seen as a threat to the other.”

Arguments tying immigration to the environment gained steam with mainstream audiences in the 1970s when the late John Tanton, an ophthalmologist from Michigan, started talking about population control. In 1997, Tanton told the Detroit Free Press that if borders weren’t secured, America would be overrun by people “defecating and creating garbage and looking for jobs.”

Tanton once chaired the Sierra Club’s National Population Committee, where he pushed the idea that overpopulation was the greatest threat to the environment.

The Sierra Club ultimately pushed back. Hop Hopkins, the club’s director of organizational transformation, said the Sierra Club has since denounced Tanton’s ideologies and advocated for immigrants’ rights.

“The Sierra Club is actively opposed to the Trump administration’s initiatives such as the southern border wall, inhumane detention and mass deportation,” Hopkins said.

Tanton went on to create a network of organizations that have pressed to limit immigration, including the Federation for American Immigration Reform, the Center for Immigration Studies and NumbersUSA.

Behind images of desert lands riddled with trash, a 2018 Center for Immigration Studies blog post noted, “Every illegal alien prevented from crossing our southern border represents about seven pounds of garbage that will no longer be left behind to potentially damage water systems, wildlife, and soil.”

Ira Mehlman, FAIR’s media director, said with nearly two million immigrants expected to cross the southern border this year, trash poses serious environmental consequences.

“These are people who are carrying everything they need on their back and they dispose of this stuff as they go, and it results in just tons of trash littering the wilderness,” Mehlman said.

On April 1, two weeks after Gosar and Westerman sent the letter to Homeland Security, U.S. Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.) appeared on a conservative talk show, warning about the environmental damage caused by migrants.

“For all of those that are concerned about the environment, we have an environmental crisis because the migrants are running across the border, they’re trampling through the ecosystem,” she said.

Blackburn, Gosar and Westerman did not respond to requests for comment.

As climate change and other environmental threats loom, Hultgren said he fears some government leaders may continue to promote the “greening of hate.” The phrase was coined by Hampshire College professor and environmental activist Betsy Hartmann to describe how the environmental movement has been used against immigrants.

The Sierra Club’s Hopkins said as environmental problems arise, some will seek to place blame.

“It doesn’t take much of an imagination to look ahead and guess the harm and bias that could come from scapegoating immigrants for the climate crisis,” Hopkins said. “It’s really a very dangerous idea that puts communities and people at extreme risk.”

By Diamond Palmer and Irene Chang

By Rebecca Holland and Ashley Capoot

For a young mother living in San Diego, the trip back to her native Mexico was supposed to be short: She needed only to complete a brief interview to obtain her green card in the United States.

For another immigrant, a 17-year-old from San Pedro Sula, Honduras, living in Michigan, the process to stay in the United States meant filling out an asylum application.

For many years, the path into the U.S. was more predictable.

But the young mother was kept from returning home because of a federal regulation, enacted in 2019, that denied immigrants entry into the U.S. based on their potential financial burden to taxpayers, according to the woman’s lawyer. The 17-year-old was rejected for leaving blank spaces on his asylum application instead of writing: “N/A.”

Both became entangled in a web of sweeping changes introduced by the Trump administration that immigration groups say dramatically slowed the immigration process in the United States — or, for tens of thousands of immigrants, stopped it in its tracks.

Over four years, the Trump administration enacted more than 1,000 immigration policies across federal agencies, including U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), according to the Immigration Policy Tracking Project.

Trump officials said the changes were meant to overhaul an immigration system that the administration believed was beset by lax enforcement and had allowed millions of undocumented immigrants into the United States.

Trump advisor Stephen Miller told Reuters last year that the administration intentionally created overlapping policies.

“In some distant, long-off future time when a Democrat is president, as we all have seen firsthand, it is a difficult, complex and time-consuming thing to remove a regulation or a longstanding memorandum,” Miller said in the interview.

Now, nearly a year into Biden’s presidency, immigration groups and legal experts say it could take months or years to sort through the rules that have separated families, blocked asylum-seekers and banned refugees from some of the most unstable countries in the world.

The Trump administration “took action in all these different areas, and in all of them to try to disrupt, and I would say, destroy, as much as possible the functioning of the immigration system without adopting any legislation,” Lucas Guttentag, a professor at Stanford and Yale universities who led the tracking project. Guttentag recently joined the Department of Justice to help advise the Biden administration on immigration policy.

San Diego-based immigration attorney Michelle Celleri said she spent months trying to bring the young mother from San Diego back into the United States, where her husband — a U.S. citizen — was waiting. The woman had traveled to Mexico with her newborn, intending to return within days.

The 2019 policy enacted by the Trump administration, however, allowed for immigrants to be denied visas or lawful permanent residency if they appeared unable to financially support themselves. Celleri said the young mother was denied because her family’s income was considered insufficient.

“I did everything I could to appeal it,” Celleri said. “They wouldn’t look at anything else. No considerations.”

A lawyer with the firm that handled the 17-year-old immigrant’s case said she is still frustrated by the rejection of the young man’s entry into the United States because of blank spaces left on his asylum application. The form had space for four siblings. He listed two.

Under a Trump policy change in 2019, some immigration applications could be denied if spaces were not filled by either a response or “N/A.”

“A child will not get the due process he is entitled to because of this absurd process,” said Susan Reed, a managing attorney at the Michigan Immigrant Rights Center, which handled the case.

Hours after taking office, Biden struck down some of the Trump administration’s most contentious immigration policies, including the so-called “Muslim ban” that turned away people from seven predominantly Muslim countries. But many Trump-era changes still stand.

No agency was more affected than U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, which grants visas and processes immigration applications. Under Trump, the agency saw 492 changes in four years through executive orders, rule changes and other non-legislative measures, according to the Tracking Project.

While executive orders can be rescinded, regulation cannot be repealed until a new regulation is written in its place, an often-lengthy process. The policy changes affected immigrants far more than Trump’s oft-contentious rhetoric did, Reed said.

“As much as Trump’s immigration policy was really populist and really ‘build the wall, rah rah,’ the biggest impact — it was very much about weaponizing a machine,” she said.

John Zadrozny, brought in under Trump as chief of staff at USCIS, defended the number of changes, calling them “pretty average,” including changes to screening and vetting asylum claims.

“When you allow a lot of fraudulent asylum claims to go through the system, people assume all claims are bad or not sincere,” he said in an interview. “A lot of people are persecuted abroad, and by cutting the fraudulent cases, we are able to help those people.”

Of hundreds of new policies enacted at USCIS, the “Public Charge Final Rule,” which would deny entry to immigrants who had used public benefits such as food stamps, public housing or Medicaid for more than a year, created particularly steep hurdles for applicants, immigration attorneys say.

“It had an enormous chilling effect that kept people from accessing government services for public health that are actually created to try to preserve public health — against the backdrop of a worldwide pandemic no less,” said Jorge Loweree, policy director with the nonprofit American Immigration Council.

Celleri, the San Diego attorney, said because the policy was introduced so quickly, some immigrants who once traveled freely in and out of the country found themselves unable to return.

“Families were separated,” Celleri said. “There was nothing anyone could have done to foresee that happening.”

The rule on blank spaces on applications also created challenges. If applicants did not have a middle name, for example, their applications risked rejection if they failed to write “N/A” in the corresponding space, Loweree said.

“The blank space policy was probably one of the most thinly veiled attempts to find any way of possibly disqualifying individuals from accessing the immigration system,” he said.

The Biden administration rescinded the so-called public charge rule in March and the blank space rule one month later.

Immigration advocates say they hope the Biden administration will also tackle a backlog of applications at the agency. As Trump’s policy changes kicked in, the backlog soared by more than 100% from 2016 to 2017, the American Immigration Lawyers Association found.

The group also found the average case processing time had grown by more than 91% since fiscal year 2014.

“Immigrant visas that aren’t used in the year they’re allocated go away,” Loweree said. “We’re just wasting visas.”

USCIS declined to comment.

House Democrats last month passed Biden’s Build Back Better Act, which pledged an historic overhaul of the U.S. immigration system. Loweree said the government needs to move quickly.

“What we’ve seen now is the Biden administration has done a whole lot on immigration, but they haven’t removed enough of those bureaucratic barriers for the system to start functioning in a more meaningful way just yet,” he said.

Madison Muller contributed to this report.

Story and photos by Madison Muller

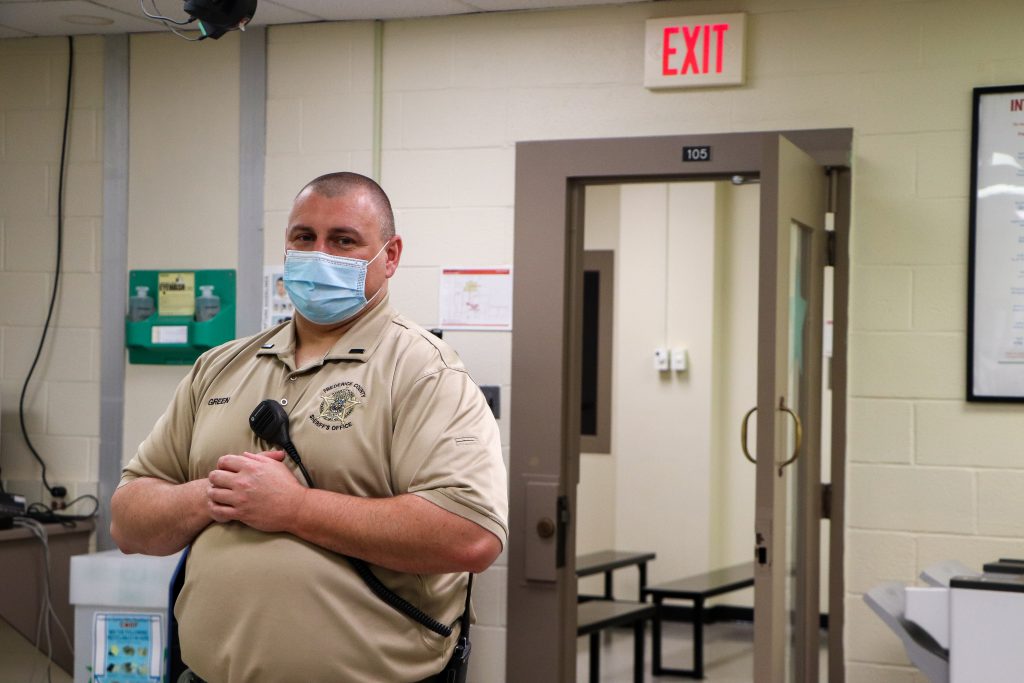

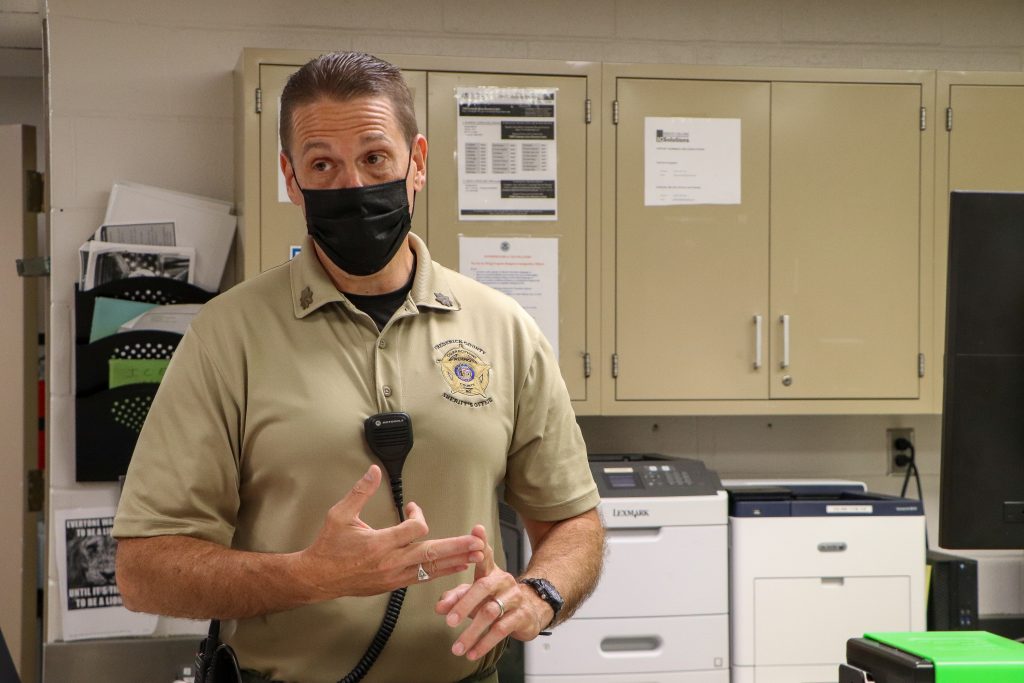

The Hall County, Georgia, Sheriff’s Department has detained undocumented immigrants on behalf of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) since 2008 as part of the county’s 287(g) agreement. Participating sheriffs say the program has led to the capture of dangerous criminals. Immigrants and their advocates have widely condemned the partnerships, saying they lead to racial profiling and the disproportionate targeting of immigrants for low-level crimes, such as traffic violations.

An undocumented man in Hall County said he has feared that seeking medical attention or performing daily tasks, such as grocery shopping, could result in his detainment and deportation.

El Carreton Taqueria, a brightly colored taco stand along Atlanta Highway has been serving a mix of authentic favorites since it opened in 1994. It’s part of the area known as “Little Mexico.”

Newspaper stands along Atlanta Highway in Gainesville, Georgia, the Hall County seat and home of thousands of immigrants, distribute Spanish-language newspapers. The area has been dubbed “Little Mexico” by residents because it has become a hub for the city’s Latinx community.

A 9-year-old watches his family members play volleyball outside his home in Gainesville. The boy’s mother worked at a local poultry plant before taking a job as a taxi driver. Taxicabs are popular in Gainesville, where many undocumented people live and work, because Georgia prohibits undocumented people from obtaining driver’s licenses.

A sign advertises employment opportunities at Foundation Food Group, one of Hall County’s many poultry plants. The ad stands next to a memorial for six employees killed in a liquid nitrogen leak inside the plant in January. Immigration advocacy groups say five of the employees were undocumented. According to a statement from the U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board in February, “The plant had been experiencing unresolved operational issues on the chicken conveyor that appear to have resulted in the accidental release of liquid nitrogen.” In a statement to Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Foundation Food Group said it trains employees for emergencies and is “committed to taking any additional measures necessary to further ensure the safety of our employees.”

A car parked outside the Gainesville office of GA Familias Unidas, an immigrant advocacy group, reads, “estamos contigo,” — “we are with you.” GA Familias Unidas provides support and resources for the Latino community, many of whom work in the city’s poultry plants.

Immigration activists in Frederick County have repeatedly raised concerns about the 287(g) agreement, signed in 2008. On a frigid night in February, protesters demanded an end to the partnership and the removal of longtime Sheriff Chuck Jenkins.

Protesters marched in February against the 287(g) program. Sheriff Jenkins said the program has helped keep violent criminals off the streets.

A Frederick County resident peers out a window to the street below, where protesters were marching. The county’s demographic has shifted in recent years, becoming increasingly diverse.

By Rebecca Holland, Monique Beals, Michael Murney and Madison Muller

Damary Gutierrez Hernandez often worries more about a busted taillight than her math and science classes at Duke University.

The 23-year-old daughter of undocumented immigrants in Northwest Georgia, Hernandez said she grew up fearing that her parents could be stopped, questioned and detained by police because of their citizenship status. Even driving created angst, she said, because Georgia bans undocumented immigrants from obtaining a license.

“They are just always so aware of where the cops could be hiding,” she said. “It’s just the constant fear of having to talk to a police person, and they ask you, ‘Oh, where were you born?’ You obviously can’t lie.”

Hernandez’s parents are among the roughly 11 million undocumented immigrants living in the shadows of mainstream America, often afraid to speak out about crime, report unsafe working conditions or stray too far from home.

Lawyers and watchdog groups say that fear intensified under President Trump, whose policy changes during his four years in office made the path to citizenship slower, harder and more expensive than ever. Dismantling those changes, experts say, could stymie policymakers for years.

Consider:

“I think for a lot of immigrant communities the last four years were pretty traumatic,” said Adonia Simpson, with the American Bar Association (ABA) Commission on Immigration. “And there’s a lot of fear or uncertainty that’s carried over into the new administration.”

President Obama deported more than three million people– more than Trump overall. But the Trump administration significantly reduced legal immigration, declining hundreds of thousands of green cards and reducing the number of non-immigrant visas by more than 11 million, the Cato Institute reported.

One Trump-era rule made it harder for immigrants who had used public benefits, such as food stamps or Medicaid, to obtain a green card. Another, dubbed the “Remain in Mexico” policy, called for certain asylum-seekers to await their hearings in Mexico even if they faced the threat of violence.

“There are a lot of things that impacted immigrants, like fear of what you said, fear of just being an immigrant, not falling out of status unknowingly or using a benefit that may jeopardize your ability to become a citizen later on,” said Sharvari Dalal-Dheini, director of government relations at the nonprofit American Immigration Lawyers Association.

Trump argued his policies would reduce “uncontrolled immigration,” protecting Americans from financial hardships and public safety risks. Before the midterm elections in 2018, about 80 percent of Republican voters said they supported his stance on immigration, according to a Reuters/Ipsos poll.

“The Democrats have increasingly migrated to a place on this issue far from where your everyday American is. The contrast is mind-boggling,” Josh Holmes, a political adviser for Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), told The Washington Post at the time.

Hours after taking office, President Biden reversed some of Trump’s more controverisal policies as well as Trump’s so-called Muslim Ban, which had banned travelers from predominantly Muslim countries from entering the United States.

Immigration advocacy groups say some changes came too late.

“The lasting legacy might be that a lot of people got deported by the Trump administration who shouldn’t have been deported, and they’re gone now, and it’ll be very hard for them to come back,” said Sarah Rich, senior supervising attorney for the Immigrant Justice Project at the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Rich and others said they hope Biden will continue to press for changes. The number of interior arrests has fallen to the lowest level in years, and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security has issued broad new directives to limit deportations.

Biden, however, has drawn criticism for the apprehension of migrants at the border and for the expulsion of over 4,600 Haitian migrants under a policy that Trump officials said was meant to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

After Vice President Kamala Harris told Guatemalan migrants, “do not come,” at a June news conference in Guatemala City, the immigration advocacy group United We Dream called the statement “disappointing and shameful” in an interview with Newsweek.

White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki told reporters at the time that the vice president was conveying that “there’s more work to be done.”

“It’s still a dangerous journey, as we’ve said many times from here and from many forums before, and we need more time to get the work done to ensure that asylum processing is where it should be,” Psaki said.

Immigration advocates say they want the Biden administration to quickly reduce a backlog of immigration and asylum applications at USCIS and create a smoother pathway to citizenship for immigrants without documentation.

Last month, House Democrats passed Biden’s Build Back Better Act, which, among other things, aims to create a more accessible path to citizenship. Biden has pledged $100 billion to reduce the application backlog and build “more humane” asylum and border processing systems.

Advocates are also calling for an end to the 287(g) program, which gives local law enforcement the power to enforce federal immigration law.

“I think there is still a deep wellspring of compassion and empathy in the American people for potential new Americans who want to come here, for whatever reason,” said Rich, the SPLC attorney. “And that does make me optimistic that any lasting legacy of the Trump administration won’t actually be so lasting.”

Irene Chang contributed to this report.

Debbie Cenziper is an associate professor and the director of investigative reporting at Medill. She also oversees the Medill Investigative Lab. Besides teaching, Cenziper is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter and nonfiction author who writes for The Washington Post. She spent three years at The George Washington University before joining the faculty of Medill.

Over the years, Cenziper’s investigative stories have exposed wrongdoing, prompted Congressional hearings and led to changes in federal and local laws. In her classes at Medill, Cenziper and her students focus on social justice investigative reporting.

Cenziper has won dozens of awards in American print journalism, including the Robert F. Kennedy Award for reporting about human rights and the Goldsmith Prize for Investigative Reporting from Harvard University. She received the Pulitzer Prize in 2007 at The Miami Herald for a series of stories about corrupt affordable housing developers who were stealing from the poor. A year before that, she was a Pulitzer Prize finalist for stories about dangerous breakdowns in the nation’s hurricane-tracking system.

Cenziper is a frequent speaker at universities, writing conferences and book events. Her first book, “Love Wins: The Lovers and Lawyers Who Fought the Landmark Case for Marriage Equality,” (William Morrow, 2016) was named one of the most notable books of the year by The Washington Post. Her second book, “Citizen 865: The Hunt for Hitler’s Hidden Soldiers in America,” was released by Hachette Books in November 2019.

Cenziper is based on Medill’s Washington, D.C. campus, working with undergraduate and graduate students on investigative stories.