By Rebecca Holland, Monique Beals, Michael Murney and Madison Muller

Damary Gutierrez Hernandez often worries more about a busted taillight than her math and science classes at Duke University.

The 23-year-old daughter of undocumented immigrants in Northwest Georgia, Hernandez said she grew up fearing that her parents could be stopped, questioned and detained by police because of their citizenship status. Even driving created angst, she said, because Georgia bans undocumented immigrants from obtaining a license.

“They are just always so aware of where the cops could be hiding,” she said. “It’s just the constant fear of having to talk to a police person, and they ask you, ‘Oh, where were you born?’ You obviously can’t lie.”

Hernandez’s parents are among the roughly 11 million undocumented immigrants living in the shadows of mainstream America, often afraid to speak out about crime, report unsafe working conditions or stray too far from home.

Lawyers and watchdog groups say that fear intensified under President Trump, whose policy changes during his four years in office made the path to citizenship slower, harder and more expensive than ever. Dismantling those changes, experts say, could stymie policymakers for years.

Consider:

- All told, the Trump administration introduced more than 1,000 immigration policies across federal agencies, according to the Immigration Policy Tracking Project. Nearly half were launched at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), the federal agency that processes immigration and asylum applications.

- The changes, which included barring immigrants considered a potential financial burden to taxpayers, were enshrined in layers of complex regulations not easily untangled.

- One of the most contentious policies — denying federal funding to so-called sanctuary cities — was upheld last year by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in New York, creating legal precedent with the potential to pave the way for lawmakers to create anti-sanctuary policies nationwide.

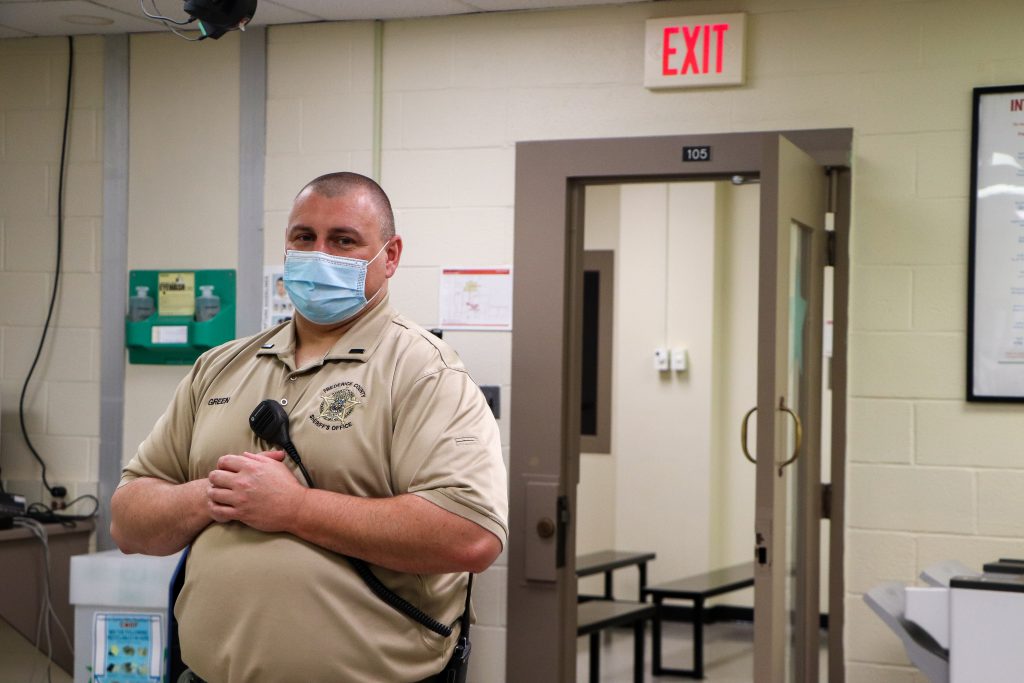

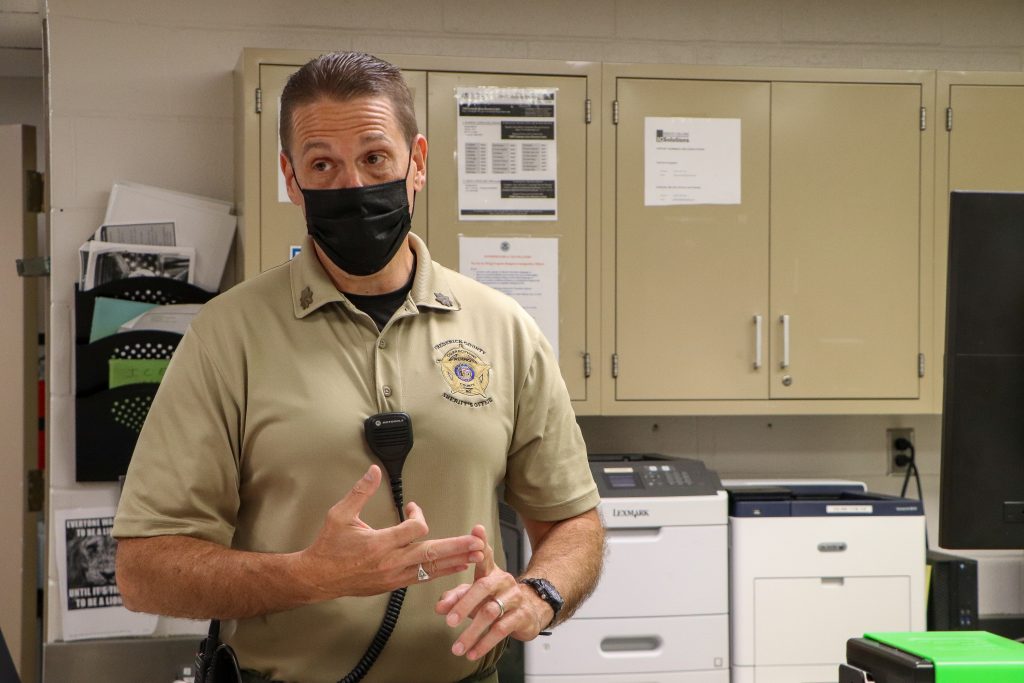

- While creating policy, the Trump administration also launched a nationwide effort to expand immigration enforcement. The number of local law enforcement agencies participating in the controversial 287(g) program to report and detain undocumented immigrants in local jails grew from 35 in January 2017 to 150 in September 2020. In North Carolina alone, the number of agreements grew from four in December 2018 to 15 today.

“I think for a lot of immigrant communities the last four years were pretty traumatic,” said Adonia Simpson, with the American Bar Association (ABA) Commission on Immigration. “And there’s a lot of fear or uncertainty that’s carried over into the new administration.”

President Obama deported more than three million people– more than Trump overall. But the Trump administration significantly reduced legal immigration, declining hundreds of thousands of green cards and reducing the number of non-immigrant visas by more than 11 million, the Cato Institute reported.

One Trump-era rule made it harder for immigrants who had used public benefits, such as food stamps or Medicaid, to obtain a green card. Another, dubbed the “Remain in Mexico” policy, called for certain asylum-seekers to await their hearings in Mexico even if they faced the threat of violence.

“There are a lot of things that impacted immigrants, like fear of what you said, fear of just being an immigrant, not falling out of status unknowingly or using a benefit that may jeopardize your ability to become a citizen later on,” said Sharvari Dalal-Dheini, director of government relations at the nonprofit American Immigration Lawyers Association.

Trump argued his policies would reduce “uncontrolled immigration,” protecting Americans from financial hardships and public safety risks. Before the midterm elections in 2018, about 80 percent of Republican voters said they supported his stance on immigration, according to a Reuters/Ipsos poll.

“The Democrats have increasingly migrated to a place on this issue far from where your everyday American is. The contrast is mind-boggling,” Josh Holmes, a political adviser for Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), told The Washington Post at the time.

Hours after taking office, President Biden reversed some of Trump’s more controverisal policies as well as Trump’s so-called Muslim Ban, which had banned travelers from predominantly Muslim countries from entering the United States.

Immigration advocacy groups say some changes came too late.

“The lasting legacy might be that a lot of people got deported by the Trump administration who shouldn’t have been deported, and they’re gone now, and it’ll be very hard for them to come back,” said Sarah Rich, senior supervising attorney for the Immigrant Justice Project at the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Rich and others said they hope Biden will continue to press for changes. The number of interior arrests has fallen to the lowest level in years, and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security has issued broad new directives to limit deportations.

Biden, however, has drawn criticism for the apprehension of migrants at the border and for the expulsion of over 4,600 Haitian migrants under a policy that Trump officials said was meant to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

After Vice President Kamala Harris told Guatemalan migrants, “do not come,” at a June news conference in Guatemala City, the immigration advocacy group United We Dream called the statement “disappointing and shameful” in an interview with Newsweek.

White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki told reporters at the time that the vice president was conveying that “there’s more work to be done.”

“It’s still a dangerous journey, as we’ve said many times from here and from many forums before, and we need more time to get the work done to ensure that asylum processing is where it should be,” Psaki said.

Immigration advocates say they want the Biden administration to quickly reduce a backlog of immigration and asylum applications at USCIS and create a smoother pathway to citizenship for immigrants without documentation.

Last month, House Democrats passed Biden’s Build Back Better Act, which, among other things, aims to create a more accessible path to citizenship. Biden has pledged $100 billion to reduce the application backlog and build “more humane” asylum and border processing systems.

Advocates are also calling for an end to the 287(g) program, which gives local law enforcement the power to enforce federal immigration law.

“I think there is still a deep wellspring of compassion and empathy in the American people for potential new Americans who want to come here, for whatever reason,” said Rich, the SPLC attorney. “And that does make me optimistic that any lasting legacy of the Trump administration won’t actually be so lasting.”

Irene Chang contributed to this report.