By Ally Mauch

As tribes and urban Indian populations scramble to tackle the opioid crisis, inaccurate data about overdose deaths has stymied health officials and frustrated tribal leaders struggling to get the help they need.

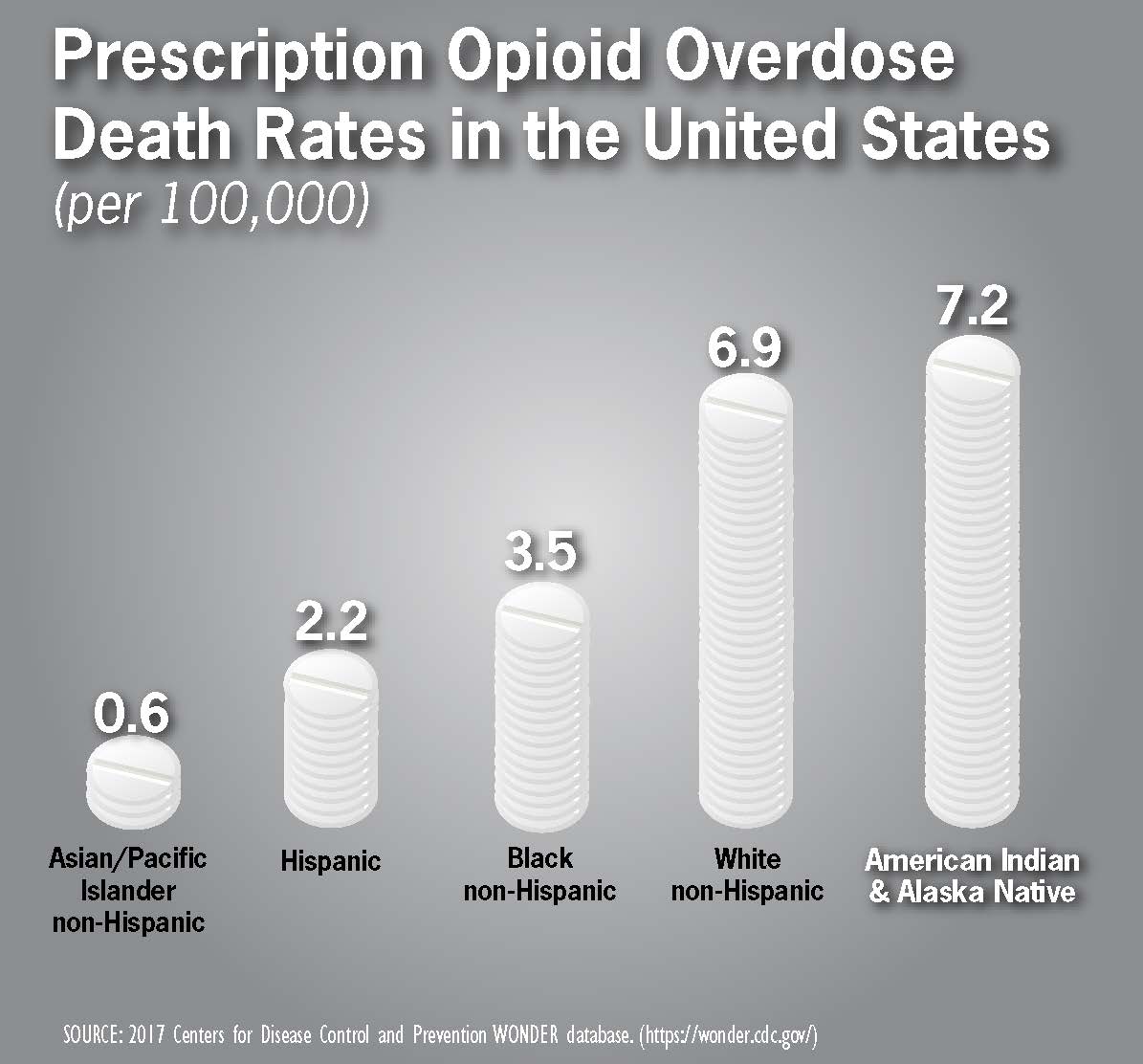

Nationwide, nearly 2,000 Native Americans died of prescription opioid overdoses from 2008 to 2017 — the highest rate of any racial or ethnic group. Experts fear the true death count is far higher.

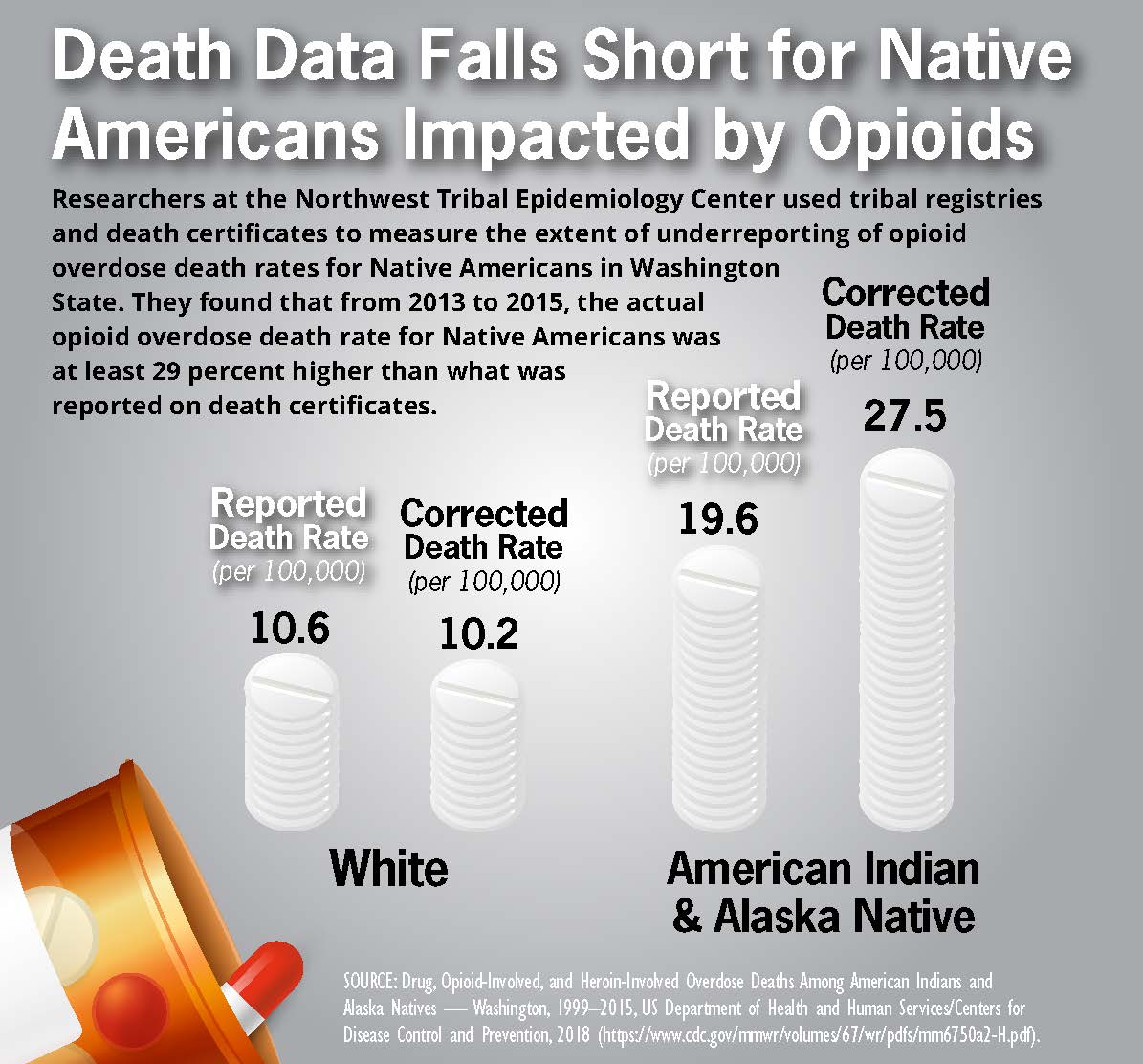

In Washington state, home to 29 federally recognized tribes, researchers in a first-of-its-kind study found that opioid overdose deaths among Native Americans were underreported by about 30 percent from 2013 to 2015. That same disparity was not found among the state’s white population.

The corrected death count showed that Native Americans were 2.7 times more likely to die from opioid-related overdoses than white people.

“When you look at health data, a lot of times you just don’t see American Indians represented at all,” said Sujata Joshi, an epidemiologist who wrote the 2018 study for the Northwest Tribal Epidemiology Center in Portland.

The problem, experts say, can be linked to death certificates. On the documents used by local, state and federal health officials, Native Americans are sometimes misclassified as “mixed race” or “other.”

The problem extends to all causes of death among Native Americans, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In a 2016 study, CDC researchers found that 40 percent of death certificates for American Indians and Alaska Natives were misclassified. The data remained “highly accurate” for other races.

Improper data — or a lack of data — can limit grant funding and other state and federal support as tribes work to battle addiction, said research scientist Linda Stanley, with the Tri-Ethnic Center for Prevention Research at Colorado State University.

“Tribes won’t get what they deserve to have because the problems are not as well- documented,” said Stanley, who has spent much of her career studying substance abuse within Native American communities.

Some tribal organizations are collecting their own data on opioid-related deaths. The United South and Eastern Tribes, made up of those in the North and Southeastern regions, has collected opioid death data for more than a decade.

The group is one of 448 tribal organizations involved in the ongoing consolidated lawsuit in Cleveland against opioid manufacturers and distributors. Like many other tribes, the group noted that correcting death-data gaps for Native Americans is essential.

“Comprehensively addressing the opioid epidemic is a major priority… including addressing the lack of resources, inadequate data, historical trauma, and other issues,” the group wrote in a court brief.

The chronic underreporting of death data has helped to marginalize Native Americans, said epidemiologist Samantha Lucas-Pipkorn of the Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Epidemiology Center in Minneapolis. The center is one of 12 granted federal funding to improve the reporting process.

“One of the ways that you can erase a population is by them not even appearing in state and federal data sets,” Lucas-Pipkorn said. “If an entire population doesn’t appear…[the government] can say that they’re not here — they don’t really exist.”

Without accurate numbers, tribal leaders say, funders will be less inclined to treat the epidemic.

Mary LaGarde, the director at the Minneapolis American Indian Center and a member of the White Earth Nation, said she fears the lack of death data has had a dramatic impact in her community. In 2016, Native Americans in Minnesota were nearly six times more likely to die of an opioid-related overdose than whites in the state.

LaGarde has been applying for grants to repave, clean and fence in a neighborhood playground littered with needles used by addicts. So far, she said, no funding has come through for the $135,000 project.

“Honestly, we don’t know where that funding is going to come from,” she said.

Lucas-Pipkorn, the epidemiologist, said the issue comes down to accurate reporting.

“Without data, there’s no way that you can advocate for your community,” Lucas-Pipkorn said. “Absolutely no way.”